THE OUTLINE OF RADIO

Chapter I

A Brief Historical Review

by John V.L. Hogan, (bio)

written in 1923

Edited By John H. Dilks (c) 1996

SCIENTISTS in many countries have helped in the development

of radio signaling; but neither the United States, Great Britain, France,

Italy, nor Germany need be unduly modest over the contributions of its

workers. A chronological record of the art's advances will skip from one

country to another; a bit suggested by one man here has been adopted and

improved upon by another investigator there, and the combination of ideas

has marked an additional step forward. Radio as we know it to-day is no

single invention or discovery; modern instruments utilize the novelties

devised by a host of engineers and physicists whose work extends over the

past seventy years or more.

In outlining the growth of radio, one hardly knows where best to begin.

It does not seem worth while to go back of the first electrical methods

of signaling. We have all heard of or seen (or perhaps experimented with)

many of the crude schemes which some writers have called “wireless telegraphy.”

Waving lanterns at night or flags by day; blowing whistles according to

some code dependent upon the number and length of the blasts; striking

stones together under the surface of a lake and listening to the sound

transmitted through the water; building huge fires visible from one mountain

top to another, -- all of these ancient plans are, in a sense, wireless

telegraphy. That is, they are forms of signaling over substantial distances

by the use of arbitrary codes, and they do not use wires connecting the

transmitting and receiving points. They are not, however, in the least

suggestive of radio, and they do not even involve electrical effects. Certainly

they contributed nothing to the growth of radio.

The

Inception of Wireless. Let us, then, begin with the first electrical

arrangement for wire-less telegraphy. It was not long before Samuel F.B.

Morse transmitted (May 24, 1844) his famous first message, “What hath God

wrought!” over the experimental telegraph wire line from Washington to

Baltimore -- indeed, quite soon after he built his earliest wire telegraph

-- that he began trying to telegraph without complete wire circuits. In

1842 he succeeded in sending messages across a canal at Washington, using

the slight conducting power of the water to carry the electric telegraph

current from one side to the other. The same plan was tried out by others

in the decade following; but although distances of nearly one mile were

covered by the use of large amounts of power, it seems never to have passed

beyond the experimental stage.

The

Inception of Wireless. Let us, then, begin with the first electrical

arrangement for wire-less telegraphy. It was not long before Samuel F.B.

Morse transmitted (May 24, 1844) his famous first message, “What hath God

wrought!” over the experimental telegraph wire line from Washington to

Baltimore -- indeed, quite soon after he built his earliest wire telegraph

-- that he began trying to telegraph without complete wire circuits. In

1842 he succeeded in sending messages across a canal at Washington, using

the slight conducting power of the water to carry the electric telegraph

current from one side to the other. The same plan was tried out by others

in the decade following; but although distances of nearly one mile were

covered by the use of large amounts of power, it seems never to have passed

beyond the experimental stage.

More

than thirty years later, in 1875, Alexander Graham Bell built his first

telephone. This surprisingly sensitive instrument could reproduce musical

signal sounds from comparatively feeble currents of electricity, and was

in many ways far superior to the receivers used by earlier investigators

of the telegraph. John Trowbridge, of Harvard University, in 1880 applied

the Bell telephone to the study of Morse's scheme of wireless telegraphy

by diffused electrical conduction through rivers or moist earth. He found

that if he interrupted the signaling current rapidly, so that its variations

could produce a musical tone, messages could be transmitted through earth

or water much more effectively than Morse had thought possible. In 1882

Bell succeeded in sending messages about a mile and a half to a boat on

the Potomac River, using his telephone receiver connected to plates submerged

below the water surface.

More

than thirty years later, in 1875, Alexander Graham Bell built his first

telephone. This surprisingly sensitive instrument could reproduce musical

signal sounds from comparatively feeble currents of electricity, and was

in many ways far superior to the receivers used by earlier investigators

of the telegraph. John Trowbridge, of Harvard University, in 1880 applied

the Bell telephone to the study of Morse's scheme of wireless telegraphy

by diffused electrical conduction through rivers or moist earth. He found

that if he interrupted the signaling current rapidly, so that its variations

could produce a musical tone, messages could be transmitted through earth

or water much more effectively than Morse had thought possible. In 1882

Bell succeeded in sending messages about a mile and a half to a boat on

the Potomac River, using his telephone receiver connected to plates submerged

below the water surface.

Developments in England. Contemporaneously with Trowbridge and

Bell, Sir William H. Preece applied to wireless signaling his knowledge

of “cross talk” between neighboring circuits carrying telephone and telegraph

messages by wire. Perhaps his first practical installation was that between

Hampshire, England, and the Isle of Wight when in 1882 the submarine cable

across The Solent (averaging a little over one mile in width), broke down.

Preece got good results in much the same way as did Morse and Bell. Preece

also experimented with the magnetic effects between circuits having no

interconnection by wire, earth, or water; and with the assistance of A.

W. Heaviside succeeded in transmitting both telegraph and telephone messages

by wireless in this way as early as 1885. However, by combining the two

arrangements and taking advantage of both magnetic induction between the

circuits and diffused conduction between their terminals, he was able to

increase working distances to more than six miles.

This

magnetic induction between completely closed circuits was only one of the

actions suggested for, and practically applied to, electric signaling without

connecting wires, during these early years. In 1885 Thomas A. Edison (bio)

(photo)

and his associates devised a different sort of wireless telegraph, which

bore a closer resemblance to the radio of to-day. Edison's proposal was

to support, high above the earth's surface and at some distance from each

other, two metallic plates. At the sending station one of these was connected

to earth through a coil that would produce a high electrical pressure;

the other, at the receiving station, was connected through a Bell telephone

to the ground. In operation, the intense electric strains produced in space

about the sending plate (by reason of its high voltage) were supposed to

extend outward as far as the receiving plate and to produce currents of

sufficient strength to give off signal tones from the telephone. A modification

of this system, by which the receiving plate was mounted on the roof of

a railway car and the telegraph wires beside the tracks were utilized to

help out the transmission, was used on the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1887.

It operated satisfactorily, and this was probably the first instance on

record of telegraphing to a moving train.

This

magnetic induction between completely closed circuits was only one of the

actions suggested for, and practically applied to, electric signaling without

connecting wires, during these early years. In 1885 Thomas A. Edison (bio)

(photo)

and his associates devised a different sort of wireless telegraph, which

bore a closer resemblance to the radio of to-day. Edison's proposal was

to support, high above the earth's surface and at some distance from each

other, two metallic plates. At the sending station one of these was connected

to earth through a coil that would produce a high electrical pressure;

the other, at the receiving station, was connected through a Bell telephone

to the ground. In operation, the intense electric strains produced in space

about the sending plate (by reason of its high voltage) were supposed to

extend outward as far as the receiving plate and to produce currents of

sufficient strength to give off signal tones from the telephone. A modification

of this system, by which the receiving plate was mounted on the roof of

a railway car and the telegraph wires beside the tracks were utilized to

help out the transmission, was used on the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1887.

It operated satisfactorily, and this was probably the first instance on

record of telegraphing to a moving train.

Signaling with Electric Waves: A New Kind of Wireless. So much

for the several types of electrical signaling, without connecting wires,

which preceded radio-telegraphy and radio-telephony. There were other suggestions,

notably those of Mahlon Loomis (1872), Professor Amos Dolbear (1886), and

Isidor Kitsee (1895); but so far as is known, none of them attained even

the degree of practical success achieved by Morse in 1842. However that

may be, all these plans dependent upon electrical conduction or induction

were utterly eclipsed soon after Guglielmo Marconi's (bio)

(photo)

experimental demonstrations of electric-wave telegraphy in 1896 and 1897.

This new form of wireless signaling, depending upon radiated electromagnetic

waves, showed so much promise and made such rapid development that interest

in the earlier types soon vanished. The new wireless art quickly gained

an importance so great that it required a characteristic name to distinguish

it from the earlier conduction and induction systems. The name given to

it is “radio communication.” Radio, therefore, is only one part of the

subject of wireless electrical signaling. It is, however, by so much the

largest and most important part that “radio” has become practically synonymous

with “wireless”, and sight has largely been lost of the fact that, strictly

speaking, radio includes electro-magnetic wave transmission and nothing

else.

The Work upon Which Radio Is Founded. Curiously enough, although

radio did not reach practical success until about 1896, its underlying

principles had been matters of scientific development for many years before.

In 1842, the same year that Morse telegraphed through the canal at Washington,

Professor Joseph Henry at Princeton University showed that the magnetic

effects of an electric spark could be detected some thirty feet away. In

1867 Professor James Clerk Maxwell, (bio)

(photo)

of the University of Edinburgh, propounded a radically new conception of

electricity and magnetism, outlined theoretically the exact type of electro-magnetic

wave that is used in radio to-day, and predicted its behavior. Twelve years

later Professor David E. Hughes discovered the sensitiveness of a loose

electrical contact, both to sounds and to electrical spark effects which

he suspected might be waves. He found it possible to indicate the passage

of electric sparks nearly one third of a mile away. But it was not until

1886 that the existence of veritable electromagnetic waves was demonstrated

beyond the possibility of misunderstanding or criticism. In that year,

Heinrich Hertz, (bio)

(photo)

working at Karlsruhe, Germany, confirmed Maxwell's theory by creating and

detecting these electric waves. With the instruments he devised, it was

possible to reflect and to focus the new waves. Their similarity to the

waves of light and heat was clearly shown.

Hertz's

electric-wave generator consisted of a spark gap to which was attached

a pair of outwardly extending conductors, corresponding in a miniature

way to the aerial and earth wires of a modern radio transmitter. His receiver

was a wire ring having a minute opening across which, when electro-magnetic

waves arrived, tiny sparks would pass. This wire ring was in some respects

like the loop receiver of today; with it Hertz was able not only to indicate

the receipt of waves, but also to determine their intensity and direction

of travel. Heinrich Hertz, despite the fact that his work was limited to

laboratory distances and that he did not suggest the use of his waves for

telegraphy, is the pioneer whose experiments laid the foundation for radio

as we now know it.

Hertz's

electric-wave generator consisted of a spark gap to which was attached

a pair of outwardly extending conductors, corresponding in a miniature

way to the aerial and earth wires of a modern radio transmitter. His receiver

was a wire ring having a minute opening across which, when electro-magnetic

waves arrived, tiny sparks would pass. This wire ring was in some respects

like the loop receiver of today; with it Hertz was able not only to indicate

the receipt of waves, but also to determine their intensity and direction

of travel. Heinrich Hertz, despite the fact that his work was limited to

laboratory distances and that he did not suggest the use of his waves for

telegraphy, is the pioneer whose experiments laid the foundation for radio

as we now know it.

A few years after Hertz's first work with invisible electro-magnetic

waves, Elihu Thomson, of Lynn, Massachusetts, proposed (1889) their use

for signaling through fogs or even through solid bodies that would shut

off light waves. Sir William Crookes in 1892 made a startling prophecy

of electric-wave telegraphy and telephony. Meanwhile, Hertz's experiments

had been taken up and extended by a number of scientists, chief among whom

were Professor Edouard Branly, of Paris; Sir Oliver Lodge, of London; and

Professor Augusto Righi, of Bologna, Italy. Branly and Lodge devised numerous

forms of “radio conductors”, or receivers utilizing some of the phenomena

also discovered by Hughes, for the delicate reception of electric waves;

Righi invented various types of wave producers and con-firmed and added

to Hertz's observations.

The Earliest Experiments with Radio. Guglielmo Marconi, who is

justly called the inventor of radio-telegraphy, was a pupil of Righi's.

To him came not merely the idea that invisible electric waves could be

used for telegraphic signaling, but also the inspiration that led to practical

solutions of the many problems involved in producing a set of sending and

receiving instruments capable of reasonably reliable operation. As early

as 1894 he recognized the defects in the indicators previously used to

show the arrival of electric waves. He applied himself to the building

of a sensitive and, for those days, dependable

device that would receive and record a message in the dots and dashes

of the Morse code. Such a receiver was made; and, having come to England,

Marconi carried on the famous Salisbury Plain demonstration in 1896. There

he telegraphed by radio a distance of nearly two miles. This spectacular

performance resulted from the sensitiveness of Marconi's new receiver,

but perhaps no less depended upon his idea of connecting one side of his

spark gap to the ground and upon his use of comparatively large elevated

or aerial conductors at both the sending and the receiving station.

Before the end of the next year (1897), Marconi had sent radio messages

to and from ships at sea over distances as great as ten miles, and between

land stations at Salisbury and at Bath, 24 miles apart, in England. This

was sufficient to settle beyond cavil the economic importance of radio-telegraphy,

and to bring to bear upon its puzzles the best scientific minds of Europe

and America. The earlier systems of wireless, none of which utilized electric

radiation, had never been capable of such results as these.

Later

Developments. In the quarter-century that has passed since Marconi

sent the first messages by radio, the complexion of the art has changed

in great measure; yet one has no difficulty in recognizing many of Marconi’s

fundamentals as they reappear in the instruments now used. The high aerial

wires at the transmitter, the ground connection, either direct or through

a wire network, as suggested by Lodge in 1898, and the invention of “tuning”

(dating from 1900) all persist in the apparatus of to-day.

Later

Developments. In the quarter-century that has passed since Marconi

sent the first messages by radio, the complexion of the art has changed

in great measure; yet one has no difficulty in recognizing many of Marconi’s

fundamentals as they reappear in the instruments now used. The high aerial

wires at the transmitter, the ground connection, either direct or through

a wire network, as suggested by Lodge in 1898, and the invention of “tuning”

(dating from 1900) all persist in the apparatus of to-day.

Marconi's original transmitter was simply an enlarged wave-producer

of the sort used by Hertz. Very soon, however, Marconi found that greater

distances could be covered by connecting one side of the generating spark

gap to an earth wire and the other to a high vertical aerial wire or antenna.

Even this form was limited in power; and the next important step seems

to have been made by dividing the sending assembly into two parts, -- a

driving circuit and a radiating circuit. Sir Oliver Lodge, in 1897, partially

applied to radio the idea of electrical tuning, the principles of which

had been stated by Professor M. I. Pupin, of Columbia University, in 1894;

but his method was greatly improved upon in 1900 by carefully adjusting

the two divisions of the transmitter to work harmoniously together. This

advance in powerful and non-interfering transmission appears to have been

made independently by Marconi and by Professor R. A. Fessenden, (bio)

(bio#2

w/photo) of the University of Pittsburgh.

Overcoming a Serious Defect. The spark

transmitter of 1900, with, of course, practical improvements, is still in quite extensive use.

The type has a number of defects, however, which will probably render it

obsolete in the not distant future. As first built, it sent out signal

energy for less than one one-thousandth of the time during which it was

supplied with power. This source of inefficiency led Fessenden, in 1902,

to invent the continuous-wave system, and to devise various ways of radiating

signal energy continuously instead of in short groups. The principal generator

of Fessenden's is the radio-frequency alternator. By 1906 he had built,

with the assistance of E. F. W. Alexanderson, (bio)

such generators in sizes capable of transmitting messages several hundreds

of miles. Since

then, Alexanderson has produced alternators large enough to work reliably

in transoceanic radio service.

with, of course, practical improvements, is still in quite extensive use.

The type has a number of defects, however, which will probably render it

obsolete in the not distant future. As first built, it sent out signal

energy for less than one one-thousandth of the time during which it was

supplied with power. This source of inefficiency led Fessenden, in 1902,

to invent the continuous-wave system, and to devise various ways of radiating

signal energy continuously instead of in short groups. The principal generator

of Fessenden's is the radio-frequency alternator. By 1906 he had built,

with the assistance of E. F. W. Alexanderson, (bio)

such generators in sizes capable of transmitting messages several hundreds

of miles. Since

then, Alexanderson has produced alternators large enough to work reliably

in transoceanic radio service.

The third general type of radio transmitter, in point of time, is the

special arc light invented by Valdemar Poulsen of Denmark. This instrument

also generates continuous streams of waves, and embodies principles used

by Elihu Thomson in 1892 and by William Duddell about 1900 for the production

of slower alternating currents. Poulsen, however, seems to have been the

first to obtain practical radio waves from an arc generator. The Poulsen

arc has been a strong competitor of the radio-requency alternator, and

is now much used for both long and short distance radio-telegraphy.

The latest and most interesting radio generator is the oscillating vacuum

tube or incandescent lamp. This device may be traced back to experimental

lamps made by Edison in 1884 and to the incandescent-lamp receiver of J.

A. Fleming, which Fleming applied to radio

reception in 1904; but it did not become a practical transmitting element

until after Lee de Forest (bio)

(photo-1940)

had added a third

electrode, called the “grid”, in 1906, and E. H. Armstrong (bio)

(photo)

had applied to it a special relay circuit in 1912. Since then, the vacuum

tube has made great progress as a transmitter, largely on account of technical

improvements made by H. D. Arnold, Irving Langmuir, W. D. Coolidge, and

others. In l9l2 vacuum tubes could be used to transmit for only a few miles,

whereas now they are produced in units rivalling the huge alternators of

the trans-Atlantic radio stations.

The Improvement of Receiving Apparatus. Turning to the development

of receivers, we find that the delicate instrument used by Marconi in 1896

was the subject of much investigation and that many other forms of “loose

contacts” were invented up to 1900 or thereabout. The erratic action of

these devices, however, forced the investigators into other channels. By

I902 Marconi had produced a magnetic detector that was entirely dependable

but not exceptionally sensitive. In the same year Fessenden patented a

uniformly operating thermal receiver of about the same sensitiveness. In

1903 Fessenden brought forward his liquid receiver, which had such great

responsiveness and stability that it was generally adopted in practical

radio and became the U. S. Navy's standard of sensitiveness. Fleming's

incandescent-lamp receiver came out in 1904, but in its original form could

not compete with the simple liquid detector. Of the “crystal” detectors,

now so common, one of the first to attain practical use was the electric-furnace

product, carborundum, which General Henry H. C. Dunwoody, of the U.S. Army,

applied to radio in 1906. Contemporaneously, G. W. Pickard found that silicon

and other substances might be utilized in the same way, and lead ore (galena)

and iron pyrites were also much used. The best of these so-called crystal

receivers were nearly equivalent in sensitiveness to the earlier liquid

type, and because of their ease of manipulation they almost entirely superseded

the older devices.

In 1906 and 1907 de Forest introduced the grid audion, which proved

to be a substantially improved form of Fleming's incandescent-lamp receiver.

This vacuum-tube detector showed surprisingly great sensitiveness from

the very first; its earlier forms were unstable, however, and it was not

accepted practically until about 1912. With the structural improvements

that followed -- the addition of the Armstrong feed-back circuit, and the

discovery (about 1913) that the same three-electrode bulb could be used

as a delicate but powerful magnifier of signal strength -- the vacuum tube

has now replaced all other receivers at stations where extreme sensitiveness

is desired. The modern forms do not closely resemble the designs of 1906;

and in special types of tube, such as those named the “magnetron” and the

“dynatron”, there is also a departure from the earlier operating principles.

All of these tubes are, however, incandescent-lamp detectors or amplifiers.

Improvements at the receiving end of radio were by no means confined

to the sensitive wave-detecting elements. The Pupin-Lodge-Fessenden-Marconi

tuning improvements were applied to receiving systems as well as to transmitters.

There was also an effort to replace the ink recorder used in Marconi's

first work. Lodge in 1897 adopted the siphon recorder, which Lord Kelvin

had devised for cable working; while other investigators (and notably those

in the United States) put the Bell telephone into use as a signal indicator

as early as 1899. In l902 Fessenden showed how the ordinary detector could

be replaced by a special telephone receiver operated by two simultaneously

transmitted streams of continuous waves. Not long thereafter he invented

the strikingly novel and ingenious “heterodyne” receiver which, with later

improvements, is well-nigh universally used in modern radio-telegraphy.

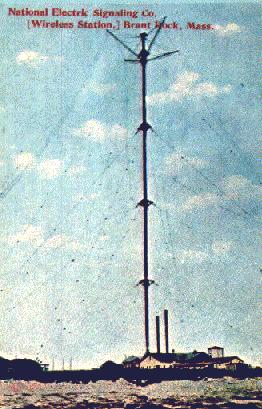

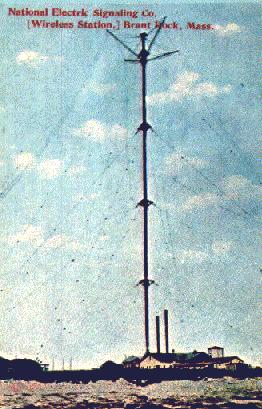

Fessenden's 430' Tower at Brant Rock.

Sending

Speech by Radio. The technical developments of radio outlined in the

preceding pages have been discussed mainly from the viewpoint of Morse

signaling, or “dot-and-dash” telegraphy, although in connection with induction

and conduction wireless the possibility of telephony has been indicated.

In the growth of radio it appears that voice transmission was not proposed

until Professor Fessenden in l9O2 suggested that his continuous-wave method

of transmission was suitable for radio-telephony. There

seems to be some evidence that Fessenden made practical trials of speaking

radio even before this date. John Stone Stone, of Boston, has stated

that, using a species of arc-lamp generator, he transmitted speech by electro-magnetic

waves early in the decade dating from 1900. It is well known, however,

that in 1906 Fessenden gave numerous practical demonstrations of radio-telephony

between his experimental stations at Brant Pock and Plymouth, Massachusetts,

and that in 1907 he increased his range from this distance of about twelve

miles to such an extent that Brant Rock was able to communicate with New

York, nearly two hundred miles away, and Washington, about five hundred

miles. In these tests it was shown that speech carried to the radio station

over a wire line could automatically be relayed to the radio and sent broadcast

on the wings of the electro-magnetic waves. At the receiving end, Fessenden

demonstrated the feasibility of transferring speech, arriving by radio,

to telephone wires and thus carrying it to a home or office remote from

the wireless installation.

Sending

Speech by Radio. The technical developments of radio outlined in the

preceding pages have been discussed mainly from the viewpoint of Morse

signaling, or “dot-and-dash” telegraphy, although in connection with induction

and conduction wireless the possibility of telephony has been indicated.

In the growth of radio it appears that voice transmission was not proposed

until Professor Fessenden in l9O2 suggested that his continuous-wave method

of transmission was suitable for radio-telephony. There

seems to be some evidence that Fessenden made practical trials of speaking

radio even before this date. John Stone Stone, of Boston, has stated

that, using a species of arc-lamp generator, he transmitted speech by electro-magnetic

waves early in the decade dating from 1900. It is well known, however,

that in 1906 Fessenden gave numerous practical demonstrations of radio-telephony

between his experimental stations at Brant Pock and Plymouth, Massachusetts,

and that in 1907 he increased his range from this distance of about twelve

miles to such an extent that Brant Rock was able to communicate with New

York, nearly two hundred miles away, and Washington, about five hundred

miles. In these tests it was shown that speech carried to the radio station

over a wire line could automatically be relayed to the radio and sent broadcast

on the wings of the electro-magnetic waves. At the receiving end, Fessenden

demonstrated the feasibility of transferring speech, arriving by radio,

to telephone wires and thus carrying it to a home or office remote from

the wireless installation.

|

Check out

Fessenden's

Speaker

Relay

Detector

Spark

Transmitter Spark

Transmitter

|

|

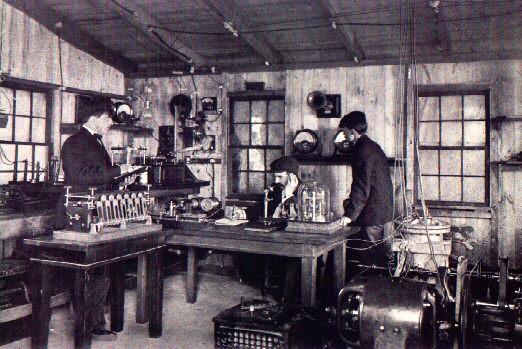

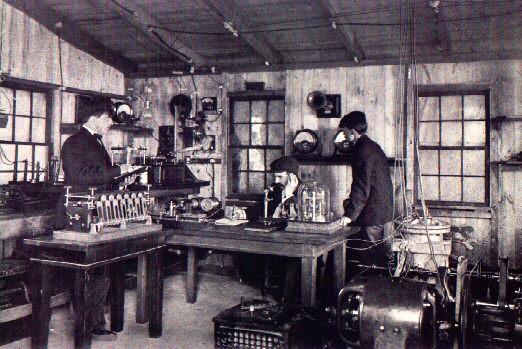

Fessenden's Brant Rock Radio-Telephone Installation

As used in the first practical experiments

in 1906. Note the alternator, the transmitters, the

glass-covered relay, and the phonograph.

This pioneer radio-frequency alternator was built by Fessenden and

Alexanderson in 1906, and generated about one kilowatt of power at 50,000

cycles per second.

|

Hear

Fessenden's

(simulated)

voice

|

From 1907 to 1912 or thereabout, radio-telephony developed slowly.

The Poulsen arc lamp was used to some extent as a power source, but proved

an unsatisfactory substitute for the generators used by Fessenden. On the

other hand, the radio alternators were expensive and bulky, and had definite

practical limitations of power and wave length. Further, and regardless

of whether arc or generator were used, the voice-controlling instruments

were not highly refined. Thus it was that when the modified incandescent

lamp was found to be a reliable wave-producer and power-magnifier, progress

in radio-telephony came with rapid strides.

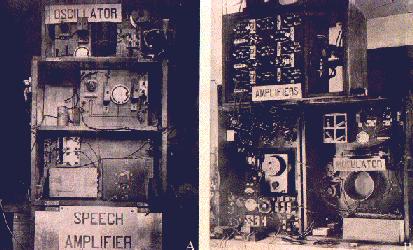

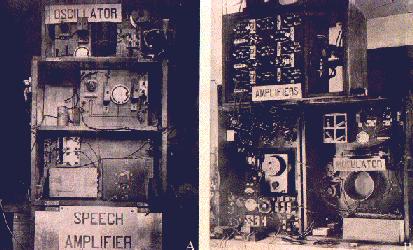

The Radio-Telephone Transmitters used at Arlington

Virginia

for the Long-Distance Experiments of 1915.

By

1915, the engineers of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company had

succeeded in talking by radio from the huge naval station at Arlington,

Virginia, to Paris, and in the opposite direction, to Honolulu. This great

experimental feat was accomplished by using vacuum tubes as oscillators

and voicemagnifiers. The power of the transmitter was utterly inadequate

to signal over so huge a distance except under the most favorable conditions,

but the work indicated possibilities which nothing but the demonstration

would have made credible. Since 1915, the trend in radio-telephony has

been toward dependable operation over shorter distances. The greatest single

advances are probably the control systems devised by R. A. Heising and

E. F. W. Alexanderson.

By

1915, the engineers of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company had

succeeded in talking by radio from the huge naval station at Arlington,

Virginia, to Paris, and in the opposite direction, to Honolulu. This great

experimental feat was accomplished by using vacuum tubes as oscillators

and voicemagnifiers. The power of the transmitter was utterly inadequate

to signal over so huge a distance except under the most favorable conditions,

but the work indicated possibilities which nothing but the demonstration

would have made credible. Since 1915, the trend in radio-telephony has

been toward dependable operation over shorter distances. The greatest single

advances are probably the control systems devised by R. A. Heising and

E. F. W. Alexanderson.

The Field of Practical Operation. To conclude this necessarily rather

sketchy historical review, a glance at progress in the application of radio

to operations, rather than its scientific growth, may be interesting. After

Marconi's demonstrations in 1897, a number of commercial installations

were made on both ship and shore. The first instance of reporting a marine

accident by radio was in Mach, l899, when the s. s. R. F. Matthews collided

with the East Goodwin light vessel. In the same year British naval vessels

communicated over distances as great as 85 miles, and the international

yacht races between the Shamrock and the Co1umbia in America,

were reported to the press by wireless. In 1901 radio stations on the Isle

of Wight and the Lizard, 196 miles apart, intercommunicated successfully;

and construction of the Poldhu (England) and Newfoundland stations for

trans-Atlantic signaling was well under way. December, 1901, marked the

first transoceanic radio signaling, for then Marconi succeeded in intercepting

repetitions of the single letter "S", in the Morse code, sent

from Poldhu to an experimental receiver at St. John's, Newfoundland The

next year, 19O2, Poldhu's signals were heard aboard the s. s. Philadelphia

over more than 2,000 miles, complete messages having been received

up to more than 1,500 miles.

In January, 1903, a trans-Atlantic radio message was sent from President

Roosevelt to King Edward VII by way of the stations at Cape Cod, Massachusetts,

and Poldhu, England; but it is not generally known whether this message

was relayed by ships on the Atlantic or whether it was received directly

from Cape Cod in complete form. A station even larger than that at Poldhu

was begun in 1905, at Clifden, Ireland, and in 1907 this plant and a twin

station at Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, were opened for a limited commercial

trans-Atlantic radio service. January 23, 1909, was the date of the collision

between the steamships Florida and Republic, which was reported

to neighboring ships by radio in time to save all the passengers and crew

of the Republic before she sank. In 1910 messages from the powerful

Clifden station were heard aboard the S. S Principessa Mafalda over

more than 6,500 miles.

On the morning of April 15, 1912, over seven hundred passengers of the

S. S. Titanic were rescued through the aid of radio when the vessel

was sunk by striking an iceberg. During the next year, radio messages were

successfully sent from and received on moving trains of the De!aware, Lackawanna

and Western Railroad. In 1914 commercial trans-Pacific radio-telegraphy

was inaugurated between San Francisco and Honolulu, and direct radio communication

between the United States and Germany was made available over the Tuckerton-Hannover

and Sayville-Nauen channels. In 1915 the United States Government took

over the operation of the Sayville and Tuckerton stations to prevent their

unneutral use. Commercial service between the United States and Japan was

begun in 1916, but development of American-European commercial communication

was prevented by the World War until after the armistice was signed on

November 11, 1918. Wartime applications of radio on aircraft, in long-distance

service, for location of ships' positions, etc., were rapidly adapted to

peaceful public uses in 1919 and 1920; the trans-Atlantic fliers in the

“NC-4” succeeded (1919) in sending messages 1,800 miles from the plane

while in the air. During 1920 and 1921 radio services with Europe were

recommenced from the newly equipped, powerful stations along the Atlantic

coast of the United States, and 1922 saw the opening and commercial use

of the largest plant in the world, located at Port Jefferson, Long Island.

In the past few years the ship-and-shore services of radio have reached

a new degree of perfection. It is now uncommon for a well-equipped vessel

to be out of communication with land at any point of the trans-Atlantic

voyage.

Broadcast Transmitter at "Old

WJZ", Newark, NJ. The first short-

wave radio-telephone transmitter

to be heard across the Atlantic.

Radio

Broadcasting. Last, but by no means least, the years 1921-1923 brought

the commencement and organization of broadcast radiotelephone services,

which send out, for whoever desires to listen, scheduled programs of music,

lectures, news bulletins, and other recreational and informative material.

More than five hundred of these broadcasting stations are in regular operation

throughout the United States. The number of listeners is estimated at well

over two million. This broadcasting of spoken words and of music is by

far the most popular application of radio. It began in November, 1920,

by the transmission of election returns from the Westinghouse station [KDKA]

at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and has spread not merely over the United

States but to other nations in a way which proves that the service meets

a true human need. Broadcast radio-telephony may not yet have the economic

value of the transoceanic or marine radio-telegraph; nevertheless, it has

aroused a great general interest in radio, and, as its character and scope

improve, it is becoming more and more strongly knit into our ways of living.

(Frank

Conrad - bio) (KDKA's

original broadcast transmitter, 1922)

Radio

Broadcasting. Last, but by no means least, the years 1921-1923 brought

the commencement and organization of broadcast radiotelephone services,

which send out, for whoever desires to listen, scheduled programs of music,

lectures, news bulletins, and other recreational and informative material.

More than five hundred of these broadcasting stations are in regular operation

throughout the United States. The number of listeners is estimated at well

over two million. This broadcasting of spoken words and of music is by

far the most popular application of radio. It began in November, 1920,

by the transmission of election returns from the Westinghouse station [KDKA]

at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and has spread not merely over the United

States but to other nations in a way which proves that the service meets

a true human need. Broadcast radio-telephony may not yet have the economic

value of the transoceanic or marine radio-telegraph; nevertheless, it has

aroused a great general interest in radio, and, as its character and scope

improve, it is becoming more and more strongly knit into our ways of living.

(Frank

Conrad - bio) (KDKA's

original broadcast transmitter, 1922)

A historical introduction is certainly no place for prophecy or speculation.

Radio is here and is doing valuable work. We now have glanced at a somewhat

broad outline of what radio is and the way in which it has reached its

present estate. Let us next find out how radio operates and what the principles

are upon which it depends.

Edited for Hypertext by John Dilks Link

back to the NJ Antique Radio Club HomePage

The

Inception of Wireless. Let us, then, begin with the first electrical

arrangement for wire-less telegraphy. It was not long before Samuel F.B.

Morse transmitted (May 24, 1844) his famous first message, “What hath God

wrought!” over the experimental telegraph wire line from Washington to

Baltimore -- indeed, quite soon after he built his earliest wire telegraph

-- that he began trying to telegraph without complete wire circuits. In

1842 he succeeded in sending messages across a canal at Washington, using

the slight conducting power of the water to carry the electric telegraph

current from one side to the other. The same plan was tried out by others

in the decade following; but although distances of nearly one mile were

covered by the use of large amounts of power, it seems never to have passed

beyond the experimental stage.

The

Inception of Wireless. Let us, then, begin with the first electrical

arrangement for wire-less telegraphy. It was not long before Samuel F.B.

Morse transmitted (May 24, 1844) his famous first message, “What hath God

wrought!” over the experimental telegraph wire line from Washington to

Baltimore -- indeed, quite soon after he built his earliest wire telegraph

-- that he began trying to telegraph without complete wire circuits. In

1842 he succeeded in sending messages across a canal at Washington, using

the slight conducting power of the water to carry the electric telegraph

current from one side to the other. The same plan was tried out by others

in the decade following; but although distances of nearly one mile were

covered by the use of large amounts of power, it seems never to have passed

beyond the experimental stage. More

than thirty years later, in 1875, Alexander Graham Bell built his first

telephone. This surprisingly sensitive instrument could reproduce musical

signal sounds from comparatively feeble currents of electricity, and was

in many ways far superior to the receivers used by earlier investigators

of the telegraph. John Trowbridge, of Harvard University, in 1880 applied

the Bell telephone to the study of Morse's scheme of wireless telegraphy

by diffused electrical conduction through rivers or moist earth. He found

that if he interrupted the signaling current rapidly, so that its variations

could produce a musical tone, messages could be transmitted through earth

or water much more effectively than Morse had thought possible. In 1882

Bell succeeded in sending messages about a mile and a half to a boat on

the Potomac River, using his telephone receiver connected to plates submerged

below the water surface.

More

than thirty years later, in 1875, Alexander Graham Bell built his first

telephone. This surprisingly sensitive instrument could reproduce musical

signal sounds from comparatively feeble currents of electricity, and was

in many ways far superior to the receivers used by earlier investigators

of the telegraph. John Trowbridge, of Harvard University, in 1880 applied

the Bell telephone to the study of Morse's scheme of wireless telegraphy

by diffused electrical conduction through rivers or moist earth. He found

that if he interrupted the signaling current rapidly, so that its variations

could produce a musical tone, messages could be transmitted through earth

or water much more effectively than Morse had thought possible. In 1882

Bell succeeded in sending messages about a mile and a half to a boat on

the Potomac River, using his telephone receiver connected to plates submerged

below the water surface. This

magnetic induction between completely closed circuits was only one of the

actions suggested for, and practically applied to, electric signaling without

connecting wires, during these early years. In 1885 Thomas A. Edison (

This

magnetic induction between completely closed circuits was only one of the

actions suggested for, and practically applied to, electric signaling without

connecting wires, during these early years. In 1885 Thomas A. Edison ( Hertz's

electric-wave generator consisted of a spark gap to which was attached

a pair of outwardly extending conductors, corresponding in a miniature

way to the aerial and earth wires of a modern radio transmitter. His receiver

was a wire ring having a minute opening across which, when electro-magnetic

waves arrived, tiny sparks would pass. This wire ring was in some respects

like the loop receiver of today; with it Hertz was able not only to indicate

the receipt of waves, but also to determine their intensity and direction

of travel. Heinrich Hertz, despite the fact that his work was limited to

laboratory distances and that he did not suggest the use of his waves for

telegraphy, is the pioneer whose experiments laid the foundation for radio

as we now know it.

Hertz's

electric-wave generator consisted of a spark gap to which was attached

a pair of outwardly extending conductors, corresponding in a miniature

way to the aerial and earth wires of a modern radio transmitter. His receiver

was a wire ring having a minute opening across which, when electro-magnetic

waves arrived, tiny sparks would pass. This wire ring was in some respects

like the loop receiver of today; with it Hertz was able not only to indicate

the receipt of waves, but also to determine their intensity and direction

of travel. Heinrich Hertz, despite the fact that his work was limited to

laboratory distances and that he did not suggest the use of his waves for

telegraphy, is the pioneer whose experiments laid the foundation for radio

as we now know it. Later

Developments. In the quarter-century that has passed since Marconi

sent the first messages by radio, the complexion of the art has changed

in great measure; yet one has no difficulty in recognizing many of Marconi’s

fundamentals as they reappear in the instruments now used. The high aerial

wires at the transmitter, the ground connection, either direct or through

a wire network, as suggested by Lodge in 1898, and the invention of “tuning”

(dating from 1900) all persist in the apparatus of to-day.

Later

Developments. In the quarter-century that has passed since Marconi

sent the first messages by radio, the complexion of the art has changed

in great measure; yet one has no difficulty in recognizing many of Marconi’s

fundamentals as they reappear in the instruments now used. The high aerial

wires at the transmitter, the ground connection, either direct or through

a wire network, as suggested by Lodge in 1898, and the invention of “tuning”

(dating from 1900) all persist in the apparatus of to-day. Sending

Speech by Radio. The technical developments of radio outlined in the

preceding pages have been discussed mainly from the viewpoint of Morse

signaling, or “dot-and-dash” telegraphy, although in connection with induction

and conduction wireless the possibility of telephony has been indicated.

In the growth of radio it appears that voice transmission was not proposed

until Professor Fessenden in l9O2 suggested that his continuous-wave method

of transmission was suitable for radio-telephony. There

seems to be some evidence that Fessenden made practical trials of speaking

radio even before this date. John Stone Stone, of Boston, has stated

that, using a species of arc-lamp generator, he transmitted speech by electro-magnetic

waves early in the decade dating from 1900. It is well known, however,

that in 1906 Fessenden gave numerous practical demonstrations of radio-telephony

between his experimental stations at Brant Pock and Plymouth, Massachusetts,

and that in 1907 he increased his range from this distance of about twelve

miles to such an extent that Brant Rock was able to communicate with New

York, nearly two hundred miles away, and Washington, about five hundred

miles. In these tests it was shown that speech carried to the radio station

over a wire line could automatically be relayed to the radio and sent broadcast

on the wings of the electro-magnetic waves. At the receiving end, Fessenden

demonstrated the feasibility of transferring speech, arriving by radio,

to telephone wires and thus carrying it to a home or office remote from

the wireless installation.

Sending

Speech by Radio. The technical developments of radio outlined in the

preceding pages have been discussed mainly from the viewpoint of Morse

signaling, or “dot-and-dash” telegraphy, although in connection with induction

and conduction wireless the possibility of telephony has been indicated.

In the growth of radio it appears that voice transmission was not proposed

until Professor Fessenden in l9O2 suggested that his continuous-wave method

of transmission was suitable for radio-telephony. There

seems to be some evidence that Fessenden made practical trials of speaking

radio even before this date. John Stone Stone, of Boston, has stated

that, using a species of arc-lamp generator, he transmitted speech by electro-magnetic

waves early in the decade dating from 1900. It is well known, however,

that in 1906 Fessenden gave numerous practical demonstrations of radio-telephony

between his experimental stations at Brant Pock and Plymouth, Massachusetts,

and that in 1907 he increased his range from this distance of about twelve

miles to such an extent that Brant Rock was able to communicate with New

York, nearly two hundred miles away, and Washington, about five hundred

miles. In these tests it was shown that speech carried to the radio station

over a wire line could automatically be relayed to the radio and sent broadcast

on the wings of the electro-magnetic waves. At the receiving end, Fessenden

demonstrated the feasibility of transferring speech, arriving by radio,

to telephone wires and thus carrying it to a home or office remote from

the wireless installation.

By

1915, the engineers of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company had

succeeded in talking by radio from the huge naval station at Arlington,

Virginia, to Paris, and in the opposite direction, to Honolulu. This great

experimental feat was accomplished by using vacuum tubes as oscillators

and voicemagnifiers. The power of the transmitter was utterly inadequate

to signal over so huge a distance except under the most favorable conditions,

but the work indicated possibilities which nothing but the demonstration

would have made credible. Since 1915, the trend in radio-telephony has

been toward dependable operation over shorter distances. The greatest single

advances are probably the control systems devised by R. A. Heising and

E. F. W. Alexanderson.

By

1915, the engineers of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company had

succeeded in talking by radio from the huge naval station at Arlington,

Virginia, to Paris, and in the opposite direction, to Honolulu. This great

experimental feat was accomplished by using vacuum tubes as oscillators

and voicemagnifiers. The power of the transmitter was utterly inadequate

to signal over so huge a distance except under the most favorable conditions,

but the work indicated possibilities which nothing but the demonstration

would have made credible. Since 1915, the trend in radio-telephony has

been toward dependable operation over shorter distances. The greatest single

advances are probably the control systems devised by R. A. Heising and

E. F. W. Alexanderson. Radio

Broadcasting. Last, but by no means least, the years 1921-1923 brought

the commencement and organization of broadcast radiotelephone services,

which send out, for whoever desires to listen, scheduled programs of music,

lectures, news bulletins, and other recreational and informative material.

More than five hundred of these broadcasting stations are in regular operation

throughout the United States. The number of listeners is estimated at well

over two million. This broadcasting of spoken words and of music is by

far the most popular application of radio. It began in November, 1920,

by the transmission of election returns from the Westinghouse station [KDKA]

at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and has spread not merely over the United

States but to other nations in a way which proves that the service meets

a true human need. Broadcast radio-telephony may not yet have the economic

value of the transoceanic or marine radio-telegraph; nevertheless, it has

aroused a great general interest in radio, and, as its character and scope

improve, it is becoming more and more strongly knit into our ways of living.

(Frank

Conrad - bio) (KDKA's

original broadcast transmitter, 1922)

Radio

Broadcasting. Last, but by no means least, the years 1921-1923 brought

the commencement and organization of broadcast radiotelephone services,

which send out, for whoever desires to listen, scheduled programs of music,

lectures, news bulletins, and other recreational and informative material.

More than five hundred of these broadcasting stations are in regular operation

throughout the United States. The number of listeners is estimated at well

over two million. This broadcasting of spoken words and of music is by

far the most popular application of radio. It began in November, 1920,

by the transmission of election returns from the Westinghouse station [KDKA]

at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and has spread not merely over the United

States but to other nations in a way which proves that the service meets

a true human need. Broadcast radio-telephony may not yet have the economic

value of the transoceanic or marine radio-telegraph; nevertheless, it has

aroused a great general interest in radio, and, as its character and scope

improve, it is becoming more and more strongly knit into our ways of living.

(Frank

Conrad - bio) (KDKA's

original broadcast transmitter, 1922)